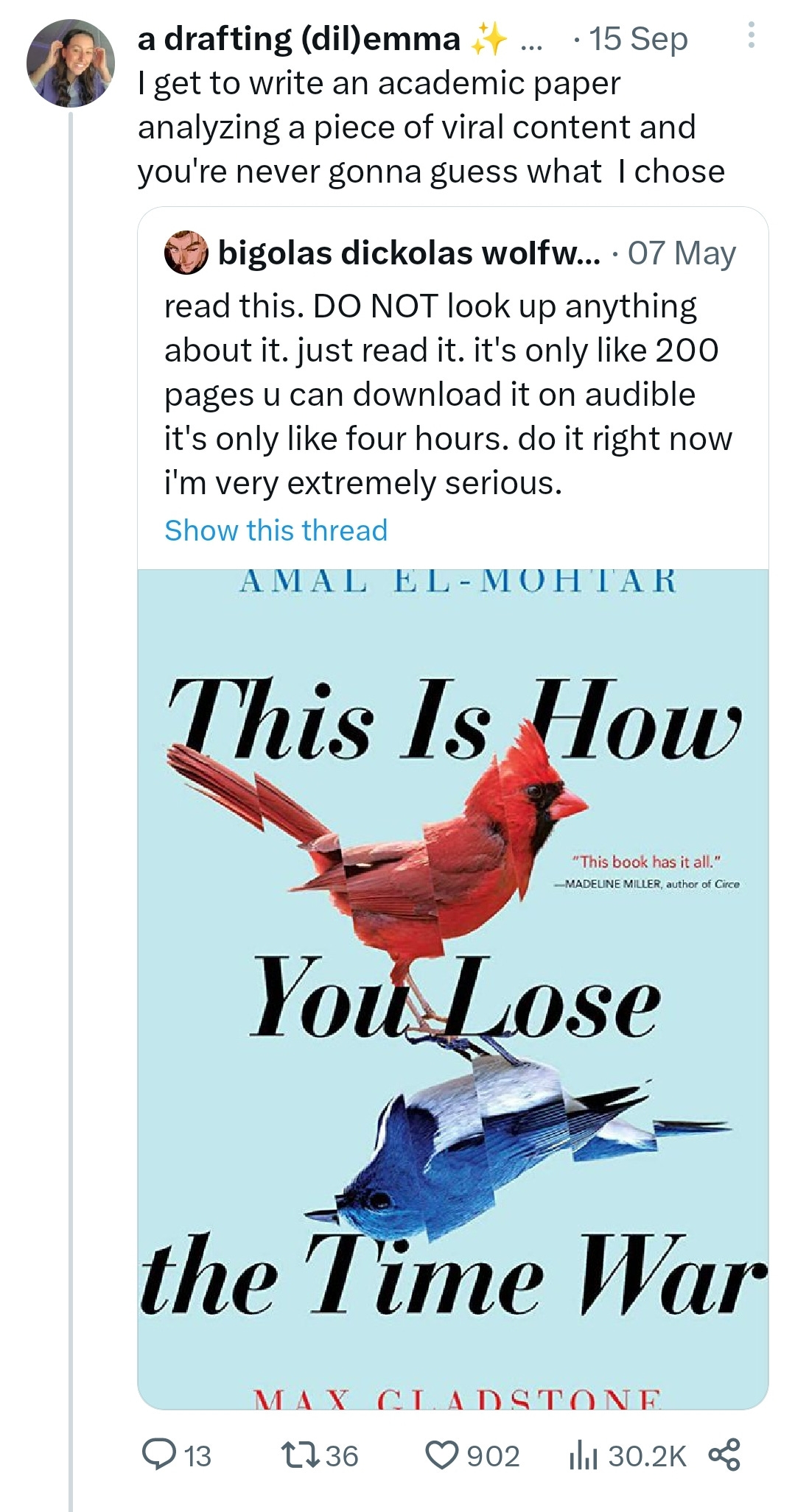

oops I wrote an academic paper on the bigolas dickolas tweet

discussing virality and consumerism through the lens of Bigolas Dickolas Wolfwood's love for This is How You Lose the Time War by Almar El-Mohtar and Max Gladstone.

Emma Tweeted WHAT?

So, funny story.

I was given the chance to write a paper on whatever viral piece of content I chose. As a totally normal non-insane person, I thought: I bet no one was writing about that time a Trigun fan account became the biggest buzz in the writing and publishing community. So I did what any totally normal non-insane person would do. I went to my professor and told them the short story about how Bigolas Dickolas became a viral sensation literally overnight. Like most people, my professor’s face was certainly surprised (if not a bit curious) about the whole thing. It’s not every day you come across some online user with a ridiculous (she says lovingly and appreciatively) name like Bigolas Dickolas Wolfwood. It definitely raised my professor’s eyebrows, as well as the people who heard what topic I was writing about. As soon as I got the approval for my paper, I instantly tweeted about my topic. Much in the fashion of Wolfwood’s original tweet, it definitely caught some people’s attention!

So, to the people who asked to read my analysis, here it is in all its absurd bigolas glory:

A Big(olas) Impact on Consumerism Through Virality

“Read this,” the viral tweet starts. “DO NOT look up anything about it. just read it… do it right now i’m very extremely serious.” The author, Bigolas Dickolas Wolfwood, who mainly uses Twitter to tweet about the 90s anime Trigun, would seem an unlikely candidate to shake up the book publishing world with a single, viral tweet about the sci-fi novel, This is How You Lose the Time War by Almar El-Mohtar and Max Gladstone. Indeed, Wolfwood was extremely serious. The tweet would amass nearly 15 million views and 130,000 likes in just under 24 hours and would drive sales for the book through the roof. The sensation of Bigolas Dickolas shows that authentic fan content can generate immense interaction causing products to go “viral” which can ultimately change how companies approach their marketing and how consumers spend their money.

“I do not understand what is happening, but I am incomprehensibly grateful to bigolas dickolas,” El-Mohtar tweeted in response to the hit tweet. A feeling reflected in most followers of this story. Engagement wasn’t the only thing this tweet managed to pull from consumers. Just three days later, Time War climbed the Amazon book charts—outranking celebrity books, the Harry Potter series, and other publishing sensations that reign on the site (Roman). Later that week when the New York Times Bestselling List released, Time War was ranked number nine. The list’s placement is determined by sales, and seeing its list at all was like seeing lightning strike repeatedly into the same bottle (Al-Mohtar). Ranking at all is incredibly unusual for a book that had been published four years prior. If a book is lucky enough to hit one of the most recognized achievements for authors in the United States, the book lists around its release date and then likely falls off. Such was not the case when it came to Wolfwood’s beloved Time War. The tweet, although ridiculous in nature and wording, somehow caught the eyes of not only consumers, but authors, literary agents, publishers, and news outlets like Slate, Business Insider, and Book Riot—all of whom published their own articles on the viral circumstances. The unique aspect of the scenario is that Wolfwood’s tweet was not done by corporate marketing, which is a probable explanation for the cause of its virality

In a newsletter written by one of the authors of Time War, they noted that even top corporate marketers at her publisher, Simon & Schuster aka one of the “Big 5” publishers in the States, have now all learned the name of Bigolas Dickolas because of how the original tweet fired up sales (El-Mohtar). It was a movement that had to be taken seriously when it earned sales by the thousands in just a few days. Especially as more people chimed in with their own support of the story, and even more sales rolled in as a result. An attractive quality of the initial post to those who engaged with it was the light-hearted phrasing of the tweet. Many online users even noted the entertaining nature of an anonymous online user with the screen name of “Bigolas Dickolas Wolfwood” starting such an uproar due to the many retweets and replies the tweet garnered in its lifetime. This presumably helped with the amount of reshares the tweet obtained since typically humorous content gets the attention on the site and not advertisements. This is the beauty of this viral tweet: it was not a product of the machine. Marketing planning had little to do with this success, only fans did.

Fandom is something often overlooked by industry leaders. They are seen as something to sell to, not for. The nature of Wolfwood’s tweet, posted online at 2 AM in early May freshly after Wolfood finished reading Time War, was something that completely ignored that formula. Authentic fan push, shared in a tweet, made consumers feel differently than traditional marketing. Jumping on the trend, genuine curiosity about the product, or even feeling like a friendly—if not unhinged suggestion—on their next read made someone click “buy!” Thus, fandom can also be credited with the success of the tweet. The initial push of engagement that the tweet earned, which would later propel it to the screens of nearly 20 million people to date, was by the anime and book community on Twitter. Their initial support of the Bigolas tweet helped boost it towards the algorithm, which is a key component of any viral piece of media. This causes one to examine the ethical approach of pushing this specific book on the global internet. In this case, Time War was not working on some ulterior agenda. Online users were not inspired to enforce a mode of thinking or opinion on others by promoting this book. Fans just wanted to speak on a book they read and, more importantly, loved.

After the tweet’s viral few weeks circulating the web, especially in the publishing and anime spheres, people continued to reference it. Even now, the original wording of the tweet is used by fans and creators to promote a piece of media they enjoyed. Those tweets receive hundreds to thousands of likes with the reference to the humor Bigolas Dickolas and Time War brought to these online spaces. Beyond that, Wolfwood didn’t just create a new internet joke for users to play off of but rather made people more conscious of marketing as a whole.

One can credit some of the tweet’s success to the absurdity of it. It gets straight to the point and then demands you to read it. It wasn’t a publisher or other seller asking this, but a fan. The humor used by Wolfwood and the author’s interactions with others online made this an exciting story to watch unfold, and one can safely imagine how the likeability of the narrative helped sell more copies of Time War. People didn’t want to feel left out of this story that was going viral, they wanted in on the narrative. They got that by picking up a copy and reading it. Consumers weren’t being sold a product, but an experience of being in on the running joke of Bigolas Dickolas Wolfwood.

The outbreak stirred up by an anime fan account exceeded Twitter and moved beyond mainstream media into the field of sales in book publishing. It sold more copies than corporate marketing divisions and prestigious book awards ever could. Top publishers seem to have met their match when it comes to selling their books and who can do it more successfully: them or a Trigun fan account. Consumers seem to love it—more eager to buy a product surrounded by a hilarious, viral sensation than one created by traditional marketing.

This paper is the property of Emma Ilene and is not subject to republication without express permission from the author.

Of course, we on book Twitter saw with our own eyes Wolfwood’s impact on publishing as a whole. I still see tweets on my timeline talking about him or even using the wording of the original tweet to promote other books. I won’t forget the time when at a convention Time War was being sold with a literal printed copy of Wolfwood’s tweet. Nor the time Wolfwood himself dressed up as his character with a huge copy of This is How You Lose the Time War strapped to his back.

Until next time,

emma (wrote what?!)